‘Demand that justice be done though the heavens fall’

By Sarah Larson

“Somebody must show that the Afro-American race is more sinned against than sinning, and it seems to have fallen upon me to do so.”

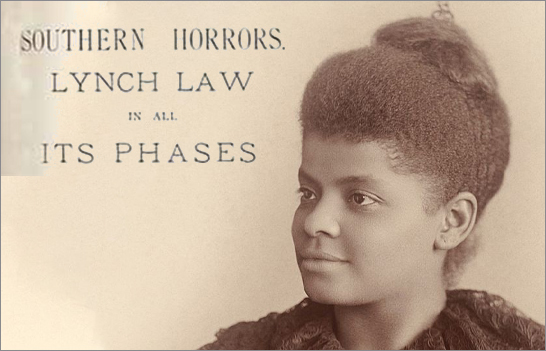

With those words, Ida B. Wells prefaces her searing work, “Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases.” Published in 1892, the pamphlet is an indictment of the lynchings perpetrated against blacks by Southern whites in the years following the Civil War. She followed up three years later with even more detailed, data-driven reporting in “The Red Record.”

Both publications were the result of intensive investigative work by Wells. She compiled eyewitness accounts and statistics regarding lynchings that had been reported in newspapers across the South and the North. The work makes her one of the first African-American women journalists in the United States, and, decades before the discipline even existed, one of the first data reporters.

As we mark Black History Month, we pause to recognize Wells, who helped to launch the anti-lynching movement of the 1890s and drew attention to the use of lynching as a means of terrorizing and controlling freed black men and women after the abolition of slavery. Wells’ investigations systematically discredited the white myth that lynching was reserved for criminals, typically black men who had been accused of raping white women.

“In ‘Southern Horrors,’ Wells made clear that white men perpetrated sexual violence against black women, while black men were brutalized by white mobs for having consensual sex with white women. And by showing that only about 30 percent of the black victims of lynch mobs had actually been accused of rape, Wells challenged the idea that lynchings resulted from it,” wrote Dr. Crystal N. Feimster, a professor of African-American studies at Yale, in a 2018 piece in the New York Times.

“She argued that the portrayal of black men as rapists put them ‘beyond the pale of human sympathy,’” Feimster wrote. “And she suggested that such a focus concealed the rape of black women. And it gave cover to whites’ violent efforts to rob African-Americans of their rights.”

Wells became an investigative journalist at a time when African-Americans were laying claim to alternative channels of mass communication. In New York in 1827, a group of free black men started the nation’s first black-owned and operated newspaper, Freedom’s Journal. “By the Civil War, 40 black newspapers were being published,” wrote Neiman Reports in a feature on the history of the black press. “And, during the 1920’s and 30’s, when major papers virtually ignored black America, the glory days of the black press began.”

Wells had been born into slavery in Holly Springs, Mississippi in 1862. She grew up during Reconstruction following the end of the Civil War, becoming a teacher to support her siblings after her parents died in a yellow fever epidemic. She moved to Memphis, and began writing articles about race and injustice that were published in newspapers nationwide.

In 1889, Wells became editor and co-owner of the Free Speech and Headlight, a black-owned newspaper founded the year before by the Reverend Taylor Nightingale and published at his Memphis church, the Beale Street Baptist Church. She was eventually fired from her teaching job because of her outspoken writings about racial inequality and focused her time and attention on newspaper writing.

The year 1892 would prove to be a crucial turning point for Wells. On March 9, a mob of white men lynched black local grocery store owner Thomas Moss, and two of his workers, Henry Stewart and Calvin McDowell. Moss had been a friend of Wells’, and in the wake of the murders, she began investigating the occurrence of lynchings across the South.

“Wells visited places where people had been hanged, shot, beaten, burned alive, drowned or mutilated. She examined photos of victims hanging from trees as mobs looked on, pored over local newspaper accounts, took sworn statements from eyewitnesses and, on occasion, even hired private investigators,” wrote The Guardian in a 2018 piece describing Wells as an “unsung heroine” of the civil rights movement. “It was astoundingly courageous work in an era of Jim Crow segregation and in which women did not have the vote.”

Wells’ investigation into lynching and its purported “causes” culminated in an impassioned editorial published on May 21, 1892, in the Free Speech. White newspapers called for retaliation, and a frenzied mob destroyed her newspaper office and press.

Wells was in New York at the time, and letters and telegrams threatened her with death if she returned. Aided by black women and allies in New York, she raised enough money to publish “Southern Horrors” a few months later, describing the work as “a contribution to truth, an array of facts, the perusal of which it is hoped will stimulate this great American Republic to demand that justice be done though the heavens fall.”

Wells later moved to Chicago, married attorney, journalist, and civil rights activist Ferdinand Barnett, and had four children. She founded civil rights organizations, including the National Association of Colored Women, and worked to secure the vote for women. She traveled across the country and internationally to denounce lynching and racial violence.

By the time of her death in 1931 at age 68, Wells had contributed to some of the leading newspapers of her era, including The New York Age, The Chicago Defender, and Chicago’s The Conservator, which she owned with her husband. Her seminal investigative reporting on racial violence changed the national narrative surrounding lynching, exposing it for the lie that it was and helping to mobilize support for civil rights.

“I consider her my spiritual grandmother,” Nikole Hannah-Jones, an investigative journalist covering civil rights said in The Guardian. “She was a trailblazer in every way … as a feminist, as a suffragist, as an investigative reporter, as a civil rights leader. She was just an all-around badass.”

For further learning, consider these resources:

“Ida B. Wells and the Lynching of Black Women,” Dr. Crystal N. Feimster, 2018

“Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases,” Ida B. Wells, 1892

“Overview of the Past 182 Years of the Black Press,” Dr. Clint C Wilson, III

“Ida B. Wells: the unsung heroine of the civil rights movement,” David Smith, The Guardian, 2018